1. The Silent Revolution at Sea

The next industrial revolution may not begin in a lab or a Silicon Valley garage. It may begin where the horizon swallows the sun—on the steel back of a cargo ship gliding through fog, silent as a floating data center adrift at sea.

For more than a century, the ocean has been powered by fire. Bunker fuel—the tar-black residue left after refining—still drives ninety percent of world trade. Every car, circuit board, and crate of avocados that crosses an ocean does so on the back of a slow-burning environmental debt. The global fleet emits more carbon than Germany, yet remains largely invisible.

But engineers and dreamers are starting to sketch alternatives. Between decarbonization mandates, collapsing battery costs, and hydrogen’s long-awaited maturity, the idea of a new maritime architecture is taking shape—one that could make the world’s largest machines not only cleaner, but electrically elegant.

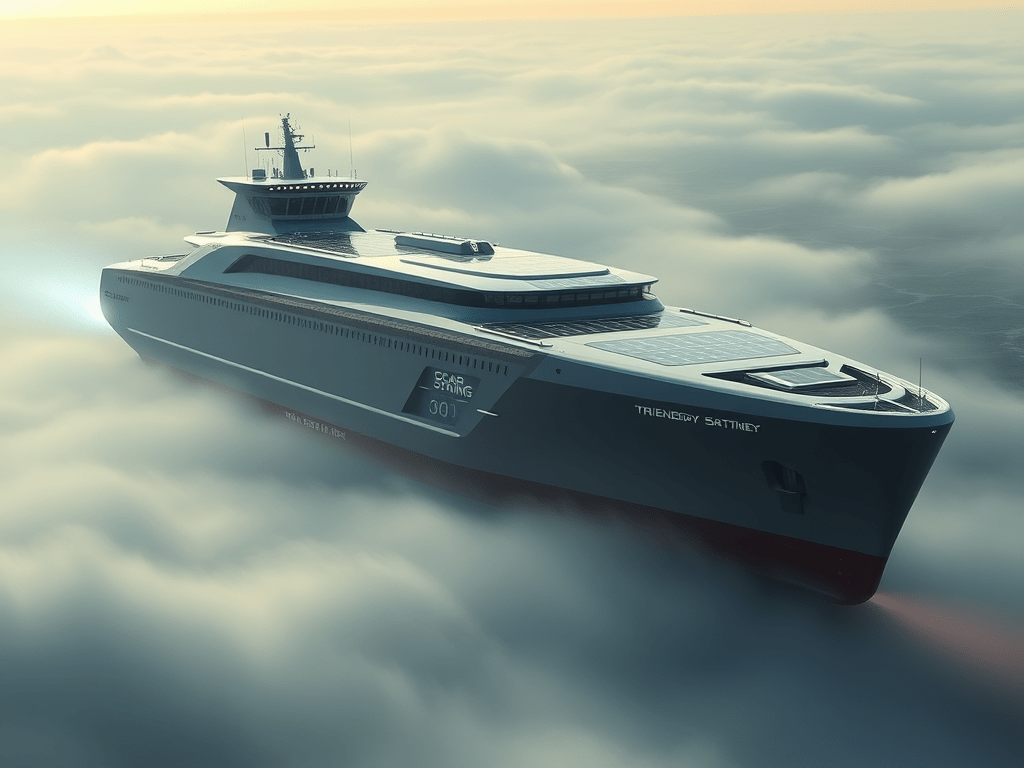

The Tri-Energy Ship exists only on paper for now: a synthesis of solar, solid-state batteries, and hydrogen backup systems imagined by designers and futurists rather than ordered by shipyards. Yet its components are real, edging closer to convergence in laboratories, policy drafts, and prototype docks. If those strands ever weave together, the silent revolution at sea will have found its vessel.

2. The Problem with the Ocean’s Carbon Habit

The math of marine energy has always mocked good intentions.

A modern bulk carrier burns roughly forty tons of fuel a day, producing over one hundred tons of CO₂. Replacing that with lithium-ion batteries would require thousands of tons of cells — enough to sink the ship before it left port.

That’s why most “electric cargo ship” headlines dissolve on contact with reality. Batteries work beautifully for ferries, not for trans-Pacific routes. Hydrogen, meanwhile, carries promise but brings its own demons: cryogenic storage at –253 °C, leakage risk, and a lack of bunkering infrastructure.

The industry faces an engineering riddle, not a moral one:

How do you move a 200-meter vessel across an ocean without dragging the weight of your own power source behind it?

The answer, now emerging from design bureaus and university test tanks, isn’t ideological purity — it’s energy pluralism.

3. The Myth of the All-Electric Ship

Electrification isn’t the problem. Monolithic electrification is.

A ship is not a car on water. Propulsion loads can exceed 50 MW for days, while life-support, refrigeration, and navigation consume megawatts more. Unlike an EV, you can’t simply pull over and plug in mid-Atlantic.

Even the best lithium cells store about 250 Wh/kg. Marine diesel? Over 12,000 Wh/kg. The gap is brutal.

That’s why early “EV ship” designs look elegant on slides but not on spreadsheets. They fail the test of physics: batteries can’t yet deliver long-duration, high-density power economically. The world needs an architecture that combines short-term electrical agility with long-term chemical stamina.

Enter solid-state batteries and hydrogen hybridization — two technologies that, when married with solar generation, solve each other’s weaknesses.

4. Enter the Tri-Energy Model

Picture a next-generation bulk carrier not as a fuel-burning engine, but as a floating power grid:

- Solar arrays line the deck and superstructure, generating 1–3 MW under clear skies — enough to run navigation systems and trickle-charge the onboard storage.

- Beneath the hull, solid-state battery rooms store tens of megawatt-hours of power. These act like ultra-safe capacitors: no flammable liquid electrolyte, no thermal runaway, twice the energy density of today’s Li-ion.

- Deep within the engine room, hydrogen fuel-cell stacks or hydrogen-fed turbines serve as the long-range generator. The hydrogen may come as liquid, ammonia, or a solid-state hydride — chemical batteries for multi-week endurance.

Together they form a seamless tri-energy loop:

- Solar → Batteries during day;

- Batteries → Propulsion during load peaks;

- Hydrogen → Electricity during long cruise phases or night runs.

Nothing burns, nothing leaks oil. The ship hums instead of roars.

It’s a design philosophy borrowed from aerospace: diversify your energy systems for resilience, not ideology.

5. The Physics of the Possible

Let’s stress-test the numbers.

A 100,000-ton bulk carrier at cruising speed needs roughly 25–30 MW continuous propulsion power.

If you covered 15,000 m² of deck with modern PV at 200 W/m², you’d generate ~3 MW in full sun — only 10% of propulsion, but enough to sustain hotel loads, cooling, and navigation.

Solid-state batteries can store 500 Wh/kg in near-term prototypes. A 2,000-ton bank would hold 1 GWh — roughly the energy to cruise for one day without hydrogen assist. Because SSBs are non-flammable and tolerant of high temperatures, they can be integrated lower in the hull, doubling as ballast.

Hydrogen’s energy density — 33 kWh/kg — shines here. Even after accounting for cryogenic storage losses, 1,000 tons of H₂ equals about 33 GWh of usable energy. That’s enough for 10–12 days of propulsion.

Blend all three and the result is astonishing:

A ship that can slow-steam for weeks, powered primarily by renewable chemistry, with solar topping off batteries daily and hydrogen extending range indefinitely.

In engineering terms, the Tri-Energy Ship doesn’t defy physics — it uses physics in harmony. Batteries deliver instantaneous torque; fuel cells deliver steady baseload; solar maintains charge equilibrium.

6. Execution, Not Magic

The hard part isn’t the idea — it’s the plumbing.

Cryogenic hydrogen systems require triple containment and ventilation protocols. Fuel cells need humidity control and heat management. Solar panels must survive salt spray, UV degradation, and hurricane-force winds.

Yet all of these are solved problems in isolation.

Norway’s MF Hydra already runs on liquid hydrogen for ferry routes. Japan has demonstrated hydrogen-ammonia co-fuel ships. Ports from Rotterdam to Yokohama are building bunkering networks.

Solid-state batteries are following the same path lithium-ion did fifteen years ago: expensive today, inevitable tomorrow. Toyota, QuantumScape, and CATL are each racing toward mass production by 2027. Maritime adaptation lags by design — but the parts are converging.

In other words: the tech clock has ticked past “if.”

The rest is execution, certification, and financing — the boring but crucial stuff.

7. The Economics of Convergence

When new energy systems converge, cost curves bend together.

Solar prices dropped 90% in fifteen years. Battery costs fell 80% in ten. Hydrogen production, now subsidized under North America’s and Europe’s clean-energy acts, is beginning its own slide.

Ships are twenty-five-year assets. Build a fossil ship in 2025, and you risk regulatory obsolescence by 2035. Build a hybrid vessel, and you get optionality — the right to pivot as tech matures.

Early models suggest Tri-Energy Ships could cut total operating emissions by 90%, fuel costs by 60%, and maintenance by 40%, thanks to fewer moving parts and modular systems. CAPEX remains high today, but amortized over fuel savings and carbon credits, parity arrives mid-2030s.

The economic story mirrors what happened in aviation when jet engines replaced pistons: higher initial cost, then unstoppable dominance once efficiency compounding kicked in.

The first fleet that perfects tri-energy architecture will not just reduce emissions — it will own the energy infrastructure of the sea.

8. The Civilization-Scale View

The deeper story isn’t about ships — it’s about how humanity learns to store light.

Solar gives us abundance; solid-state batteries give us immediacy; hydrogen gives us endurance. Together they represent the first truly global, renewable energy stack — adaptable from rooftop to rail yard to ocean liner.

A Tri-Energy Ship is more than a vehicle. It’s a symbol of pluralistic engineering — an admission that no single energy form can carry civilization alone. The future belongs to systems that cooperate, not compete.

And maybe that’s the quiet poetry of it:

While nations argue about fuels and markets, a vessel somewhere on the Pacific may glide across the water, powered by sunlight captured days ago, stored as ions in a solid lattice, and rekindled as hydrogen fire in a fuel cell’s heart — a living circuit connecting sky, sea, and human design.

Epilogue: Execution Will Decide

Technology tends to move in three phases: disbelief, proof, inevitability.

Hydrogen is crossing from phase two to three. Solid-state batteries are following close. Solar is already there.

The next decade will determine whether these threads braid into a maritime revolution or another beautiful blueprint stranded by inertia.

If the world builds it — if ports anchor hydrogen hubs, if regulators price carbon sanely, if engineers finish what physics allows — then the Tri-Energy Ship will be more than a metaphor. It will be the next silent revolution at sea.

Disclaimer

This is AI generated content. This essay reflects speculative engineering foresight, not financial or investment advice. It blends publicly known research trends, prototype data, and conceptual extrapolation to illustrate potential energy convergence scenarios in maritime technology.

Leave a comment